Si hay algo que sintetiza el aporte de la escuela francfurtiana es el ensamble de sociología y filosofía. De ahí la importancia del flaneur que, caminando la ciudad con el ojo atento a lo que ocurre, arma un puzzle que puede darnos claves sobre la existencia. En el caso de Claudio Larrea y su muestra “Porteños” ese ojo es la cámara de fotos: como un cazador, va apropiándose de cruces inefables entre ciudad y ciudadano, anclado en la tradición del Horacio Coppola de Buenos Aires 1936.

Hay más de una toma en la que el hombre es una referencia aparentemente nimia, y por eso mismo potente, en medio de un paisaje urbano amplificado: alguien que trepa por el obelisco y parece una arañita recortada sobre la pared blanca, un cielo cargado de nubes y la torre del clásico edificio del Trust Joyero Relojero; chicos jugando a la pelota en una azotea entre cientos de edificios grises, medianeras leprosas y cables de alumbrado; una persona solitaria que se baja de su bicicleta para hablar por su teléfono celular bajo una enorme columna con un león alado; dos personas tomando sol delante del Palacio Pizurno; un hombre convertido en un pequeño punto al pie de la subida de un garaje; hombres leyendo en un bar con piso ajedrezado, mientras el viento levanta las cortinas. ¿De qué nos hablan estas escenas sino de un desnivel de escalas? ¿De qué nos hablan sino de la asimetría entre el hombre y su entorno? Buenos Aires, una ciudad caminable, amoldada al pie humano, es el sitio donde ese hombre se siente cómodo. En las fotos de Larrea hay una exaltación secreta del individuo: es a la vez un asterisco y la terminal nerviosa por donde cruza lo significativo, lo considerable.

Dicen que la censura aguza la imaginación. Un subproducto de esa afirmación, a partir de la prohibición del retrato directo sin consentimiento, es la riqueza que adquieren los personajes con las caras tapadas (por zapallos, por pasamontañas o por un fonógrafo en venta) o directamente de espaldas. La ventaja es la ambigüedad, lo no dicho, lo que se puede entrever, como en esas espesas cabelleras que parecen manojos de alambres electrificados.

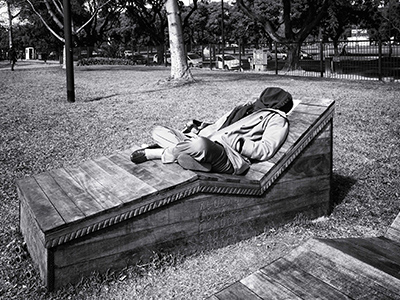

Hay por fin una serie de imágenes que introducen, no sin ironía, lo religioso y lo metafísico en la vida cotidiana: se inscriben en este registro una suerte de pantalla partida con una mujer tomando sol, a la derecha, mientras del otro lado caminan dos monjas totalmente tapadas con sus ropas características; el homeless musulmán tirado al lado de un cartel que pone en entredicho la educación; judíos ortodoxos cuya aparente formalidad anacrónica contrasta con un cartel que habla del tiempo y la cicatriz de la chapa municipal faltante; o, por fin, el cura concentrado en la publicidad de un aperitivo.

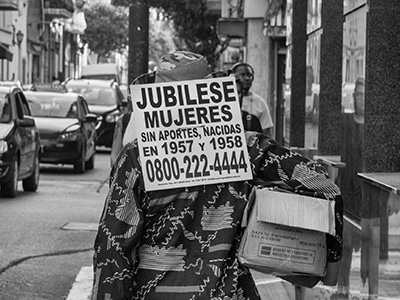

Otras escenas aluden a la degradación política de un país que no mira hacia adelante: una parada de colectivos vandalizada, con una pasajera esperando; pensionados protestando; un chico esgrimiendo un cartel publicitario de una gestoría que invita a acogerse a la jubilación sin aportes; una extraña manifestación al lado de una camioneta destartalada; un premonitorio vendedor de copitos que recuerda la explosión de un hongo nuclear. Tal vez pueda inscribirse en este lote, como condensación simbólica, la fotografía de una mujer intentando moverse dentro de un colectivo lleno y con una remera que tiene un ojo en la espalda.

Juan José Sebreli y Marcelo Gioffré, 2023

If there is something that synthesizes the contribution of the Frankfurt school, it is the ensemble of sociology and philosophy. Hence the flaneur importance that, while walking the city with an attentive eye to what is happening, builds a puzzle that gives us clues about existence. In the case of Claudio Larrea and his exhibition "Porteños" that eye is the camera: like a hunter, he goes appropriating the ineffable crosses between city and citizen, anchored in the tradition of the Horacio Coppola from Buenos Aires 1936.

There is more than one shot in which the man is an apparently insignificant reference, and therefore potent, in the middle of an amplified urban landscape: someone who climbs up the obelisc and looks like a little spider silhouetted against the white wall, a sky full of clouds and the tower of the classic building of the Jeweler Watchmaker Trust; boys playing ball on a rooftop among hundreds of grey buildings, leprous party walls and lighting cables; a lonely person who gets off his bike to talk on his cell phone under a huge column with a winged lion; two people sunbathing in front of the Pizzurno Palace; a man turned into a small dot at the bottom of a garage ascent; men reading in a bar with a checkered floor, while the wind raises the curtains. What do these scenes tell us about if not a difference in scales? What are they talking about if not the asymmetry between man and his environment? Buenos Aires, a walkable city, molded to the human foot, is the place where that man feels comfortable. In Larrea's photos there is a secret exaltation of the individual: it is both an asterisk and the terminal nerve through which the significant, the considerable crosses.

They say that censorship sharpens the imagination. A by-product of this affirmation, based on the prohibition of direct portraits without consent, is the richness that the characters acquire with their faces covered (by pumpkins, ski masks or a phonograph on sale) or directly from behind. The advantage is ambiguity, what is not said, what can be glimpsed, as in those thick hair that look like bundles of electrified wires.

There is finally a series of images that introduce, not without irony, the religious and the metaphysical in everyday life: a kind of split screen is inscribed in this register with a woman sunbathing on the right, while on the other side two walking nuns completely covered with their characteristic clothes; the homeless Muslim lying next to a poster that questions education; orthodox Jews whose apparent anachronistic formality contrast with a poster that talks about time and the scar of the missing municipal plate; or, finally, the priest concentrating on an aperitif advertising.

Other scenes allude to the political degradation of a country that does not look forward: a vandalized bus stop, with a waiting passenger; pensioners protesting; a boy brandishing an advertising poster for an agency that invites people to take advantage of retirement without contributions; a strange demonstration next to a beat-up van; a premonitory cotton candy seller that recalls the explosion of a nuclear mushroom cloud. Perhaps the photograph of a woman trying to move inside a crowded bus and wearing a T-shirt with an eye on the back may be included in this lot as a symbolic condensation.

Juan José Sebreli and Marcelo Gioffré, 2023